Choose Language

January 13, 2022

NewsUS Inflation hits 7%: What might the Fed do next?

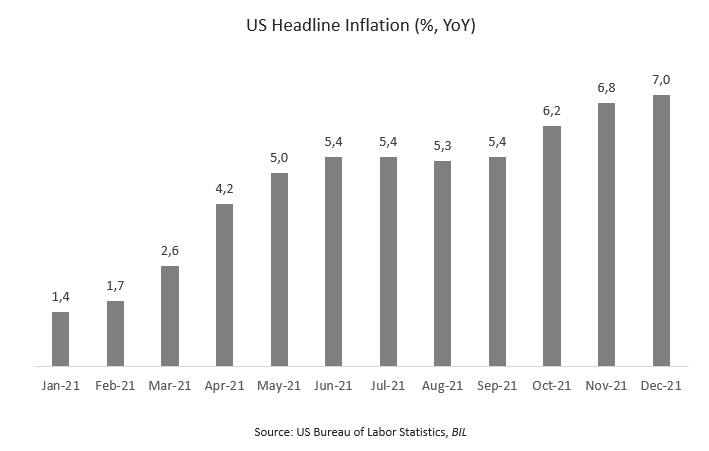

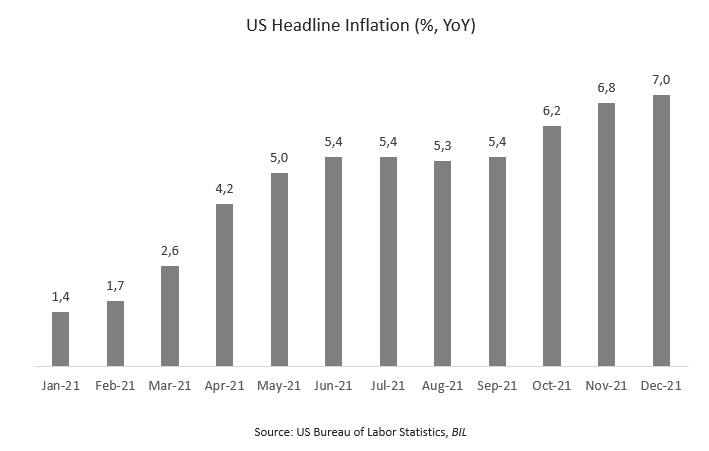

- US headline inflation rises 7% in December, core inflation by 5.5%

- Labour market tightness continues

- With the taper being old news and rate hikes now aggressively priced in by the market, the Fed may need to revert to a different kind of ammunition in order to anchor inflation expectations

- The new hot topic is a reduction of the Fed balance sheet

On Wednesday, data showed that US inflation continued to heat up in December. The year-on-year change in headline prices was the most elevated since 1982 (at +7.0%), and the highest since 1991 for the core index (+5.5%), which excludes volatile components such as food and energy. Gains were primarily driven by core goods with continued upside in used car prices (up 3.5% from the previous month, and nearly 40% from a year ago), new car prices (+1.0%) and clothing (+1.7%).

With Americans having lived with inflation above 5% for seven months now, and with some analysts arguing that the Fed is behind the curve, this latest print supports earlier and faster Fed rate hikes, potentially followed by an unwinding of its $8.8 trillion balance sheet.

However, the Fed has a dual mandate and must balance its symmetrical 2% inflation target with its quest to achieve maximum employment. If it acts too aggressively, it could choke off growth and deter companies from hiring.

The influencer market for branded and platform deals is projected to skyrocket to $28 billion by 2026. A major driver of success is coming from platforms like Instagram, TikTok, Facebook, YouTube, and Twitch [2]

While the unemployment rate has plummeted to 3.9% (below the Fed’s 4% long-run rate), there are still 3.6 million fewer workers in the US than before the pandemic. Americans have left the labour force in hoards in what some have coined “The Great Resignation” (if you are not in the labour force and not looking for work, you’re not included in the unemployment rate calculation). The problem is, a large share of the potential workforce isn’t applying to jobs. Many would-be workers have filed for early retirement, remain fearful of the virus, are caring for children at home or have re-evaluated their priorities in terms of work, life and purpose. This is not to mention the self-employed and the new digital economy made up of influencers and creators monetizing their ‘skills’ or ‘brands’ online and outside of payroll data: In 2021, TikTok surpassed Google in terms of internet traffic!

All this has resulted in intense competition amongst companies for a smaller pool of workers, putting upwards pressure on wages. Average hourly wages rose 4.7% in December from a year earlier, well above the roughly 3% average increase before the pandemic. While most of these increases had been concentrated in contact-intensive, low-paid jobs like hospitality, wage pressures are beginning to broaden out, posing the risk that inflation becomes “entrenched”.

Fed Chair Jerome Powell has warned that entrenched inflation could jeopardise the economic recovery and noted that “to get the very strong labour market we want with high participation, it is going to take a long expansion… to get a long expansion, we are going to need price stability. ” He added, “high inflation is a severe threat to achieving maximum employment and to achieve the long expansion that could give us that.”

So what might the Fed do?

It is becoming crucial that the Fed anchors inflation expectations as they tend to translate into higher actual inflation. Tapering of the central bank’s bond buying is essentially old news. At the December FOMC, acknowledging that its inflation mandate had been satisfied and that the “risk of higher inflation becoming entrenched has increased”, the Fed announced that it would double its pace of tapering from $15bn to $30bn per month, indicating that asset purchases should draw to a close completely by mid-March. At the same time, rate hikes are now aggressively priced in the market, with economists generally expecting the Fed to raise interest rates in March, with two or three more hikes later in the year.

An additional tool that has been brought to the drawing board is quantitative tightening (QT) – i.e. a reduction in its $8.8 trillion balance sheet. The minutes from the December FOMC mention:

“Some participants judged that a significant amount of balance sheet shrinkage could be appropriate over the normalization process, especially in light of abundant liquidity in money markets and elevated usage of the ON RRP[1] facility.” No details around the how and when of any potential QT have been released and for now, this seems to be posturing. Nonetheless, it caused a bout of market anxiety.

The last instance when the Fed managed to reduce its balance sheet substantially was from 2017 to 2019 with a total reduction of 15%. Looking at historical data we see that during this period the S&P 500 actually delivered almost 25% returns and bond indices also managed to deliver a decent performance. However, under the surface, this also pushed up the short-term funding rate and in September 2019, a shortage of cash in the system led to the repo market crisis. This time around, the Fed is comfortable to argue that its new Standing Repo Facility should help avert a repeat of the liquidity squeeze.

As of today, inflation and GDP growth are now much higher compared to 2017 (GDP: 5% vs 2.1%; inflation: 7% vs 1.7%) and the unemployment rate is similar, rendering quicker action on the Fed’s behalf intuitive. The big difference between now and then is the lingering participation rate, as well as the speed at which policy is changing. This time, the span between the beginning of tapering, the first rate hike and balance sheet reduction could be less than one year while in the past, it took years to fully normalize monetary policy.

The Fed Chair reassured markets this week, painting a picture of a soft landing, saying that the Fed can cool inflation without damaging labour market and by being “humble but a bit nimble". The latest minutes mention that “Some participants commented that removing policy accommodation by relying more on balance sheet reduction and less on increases in the policy rate could help limit yield curve flattening during policy normalization”. However, the unprecedented speed of policy normalization could indeed catalyze higher volatility and style and sector considerations will become ever more crucial. The key takeaway is that the age of ultra-loose monetary policy is coming to an end and the investment landscape is set to become more demanding than it has been in the last few years.

[1] Overnight reverse repurchase agreement, also called a “reverse repo” or “RRP”

[2] Where Influencer Marketing and the Creator Economy Are Headed in 2022 and Beyond | Inc.com

Disclaimer

All financial data and/or economic information released by this Publication (the “Publication”); (the “Data” or the “Financial data

and/or economic information”), are provided for information purposes only,

without warranty of any kind, including without limitation the warranties of merchantability, fitness for a particular

purpose or warranties and non-infringement of any patent, intellectual property or proprietary rights of any party, and

are not intended for trading purposes. Banque Internationale à Luxembourg SA (the “Bank”) does not guarantee expressly or

impliedly, the sequence, accuracy, adequacy, legality, completeness, reliability, usefulness or timeless of any Data.

All Financial data and/or economic information provided may be delayed or may contain errors or be incomplete.

This disclaimer applies to both isolated and aggregate uses of the Data. All Data is provided on an “as is” basis. None of

the Financial data and/or economic information contained on this Publication constitutes a solicitation, offer, opinion, or

recommendation, a guarantee of results, nor a solicitation by the Bank of an offer to buy or sell any security, products and

services mentioned into it or to make investments. Moreover, none of the Financial data and/or economic information contained on

this Publication provides legal, tax accounting, financial or investment advice or services regarding the profitability or

suitability of any security or investment. This Publication has not been prepared with the aim to take an investor’s particular investment objectives,

financial position or needs into account. It is up to the investor himself to consider whether the Data contained herein this

Publication is appropriate to his needs, financial position and objectives or to seek professional independent advice before making

an investment decision based upon the Data. No investment decision whatsoever may result from solely reading this document. In order

to read and understand the Financial data and/or economic information included in this document, you will need to have knowledge and

experience of financial markets. If this is not the case, please contact your relationship manager. This Publication is prepared by

the Bank and is based on data available to the public and upon information from sources believed to be reliable and accurate, taken from

stock exchanges and third parties. The Bank, including its parent,- subsidiary or affiliate entities, agents, directors, officers,

employees, representatives or suppliers, shall not, directly or indirectly, be liable, in any way, for any: inaccuracies or errors

in or omissions from the Financial data and/or economic information, including but not limited to financial data regardless of the

cause of such or for any investment decision made, action taken, or action not taken of whatever nature in reliance upon any Data

provided herein, nor for any loss or damage, direct or indirect, special or consequential, arising from any use of this Publication

or of its content. This Publication is only valid at the moment of its editing, unless otherwise specified. All Financial data and/or

economic information contained herein can also quickly become out-of- date. All Data is subject to change without notice and may not be

incorporated in any new version of this Publication. The Bank has no obligation to update this Publication upon the availability of new data,

the occurrence of new events and/or other evolutions. Before making an investment decision, the investor must read carefully the terms and

conditions of the documentation relating to the specific products or services. Past performance is no guarantee of future performance.

Products or services described in this Publication may not be available in all countries and may be subject to restrictions in some persons

or in some countries. No part of this Publication may be reproduced, distributed, modified, linked to or used for any public or commercial

purpose without the prior written consent of the Bank. In any case, all Financial data and/or economic information provided on this Publication

are not intended for use by, or distribution to, any person or entity in any jurisdiction or country where such use or distribution would be

contrary to law and/or regulation. If you have obtained this Publication from a source other than the Bank website, be aware that electronic

documentation can be altered subsequent to original distribution.

As economic conditions are subject to change, the information and opinions presented in this outlook are current only as of the date

indicated in the matrix or the publication date. This publication is based on data available to the public and upon information that is

considered as reliable. Even if particular attention has been paid to its content, no guarantee, warranty or representation is given to the

accuracy or completeness thereof. Banque Internationale à Luxembourg cannot be held liable or responsible with respect to the information

expressed herein. This document has been prepared only for information purposes and does not constitute an offer or invitation to make investments.

It is up to investors themselves to consider whether the information contained herein is appropriate to their needs and objectives or to seek advice

before making an investment decision based upon this information. Banque Internationale à Luxembourg accepts no liability whatsoever for any investment

decisions of whatever nature by the user of this publication, which are in any way based on this publication, nor for any loss or damage arising

from any use of this publication or its content. This publication, prepared by Banque Internationale à Luxembourg (BIL), may not be copied or

duplicated in any form whatsoever or redistributed without the prior written consent of BIL 69, route d’Esch ı L-2953 Luxembourg ı

RCS Luxembourg B-6307 ı Tel. +352 4590 6699 ı www.bil.com.

Read more

More

July 3, 2025

NewsThe clock is ticking on EU-US trade n...

This article was written on July 1 The July 9 deadline by which US trading partners must have reached a trade deal with the...

July 1, 2025

BILBoardBILBoard Summer 2025 – Always wear su...

From the brink of a bear market, US stocks have staged a ten-trillion-dollar rally, bringing record highs within reach. Summer is in full swing in...

June 24, 2025

NewsAfter the shipping surge: What’s next...

As the world grappled with the threat of tariffs from the United States, global trade experienced a dramatic yet short-lived boom. Now, as the dust...

June 20, 2025

Weekly InsightsWeekly Investment Insights

Saturday 21 June marks the summer solstice in the Northern Hemisphere. This is the day with the most daylight hours in the year and...

June 16, 2025

Weekly InsightsWeekly Investment Insights

The short week kicked off with a thaw in trade tensions between the US and China as representatives from the world’s two largest economies...